Fixing Bottlenecks in Lead Pipe Funding: Minimum Allotment Requirements

The clock continues ticking for federal Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) lead service line (LSL) replacement dollars. With Federal Fiscal Year (FFY) 2025 allotments still pending, states are left waiting.

IIJA dedicated $15 billion for identifying and replacing LSLs, distributed in $3 billion annual chunks across FFYs 2022–2026. The first three years of funding have already been allotted, but the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has yet to announce FFY2025 allotments. That delay matters: states have only until the end of the following fiscal year (i.e., September 30, 2026), to request these funds, and just one year after that to commit them to projects (see: EPIC’s State Revolving Fund (SRF) Flow of Funds explainer). Every month of delay shortens the window for states to use these funds and makes it harder for water utilities to plan large-scale replacement projects that lower costs through economies of scale

In a previous blog, we outlined three key bottlenecks slowing down LSLR funding. Here, we take a closer look at the first one: minimum allotment requirements, and why waiving them for LSL-specific funds could help these dollars flow more efficiently to the communities that need them most.

How the Allotment Process Works

Under the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA), EPA must first ensure that each state – and Washington D.C.– receives at least 1% of DWSRF funds and that 1.5% is allotted across all U.S. territories. It then distributes the remaining funds according to assessed needs (see EPIC’s IIJA LSLR allotment explainer) based on each state’s share of national LSLs.

While unused dollars can eventually be reallotted to high-burden states, redistribution can only happen after a two-year availability period closes, leaving high-need states waiting while dollars sit idle.

The result? A slow drip of funding.

What Would Happen Without the Minimum Requirement?

Minimum allotments are a common feature of federal funding. They’re designed to make sure every state is able to cover broad, ongoing needs. However, LSL replacement isn’t like most other water infrastructure projects. It is a discrete, one-time intervention: one lead pipe comes out, and a non-lead pipe goes in. In addition, replacement activity tends to be concentrated in areas with older infrastructure, especially in the Midwest and Northeast, rather than distributed evenly across all systems.

In fact, because of the minimum cap on allotments, states with relatively few LSLs often receive far more money than they need. That’s why the same minimum funding requirement may not be appropriate for LSL replacement. Instead, dollars should flow directly to the states carrying the heaviest lead burdens.

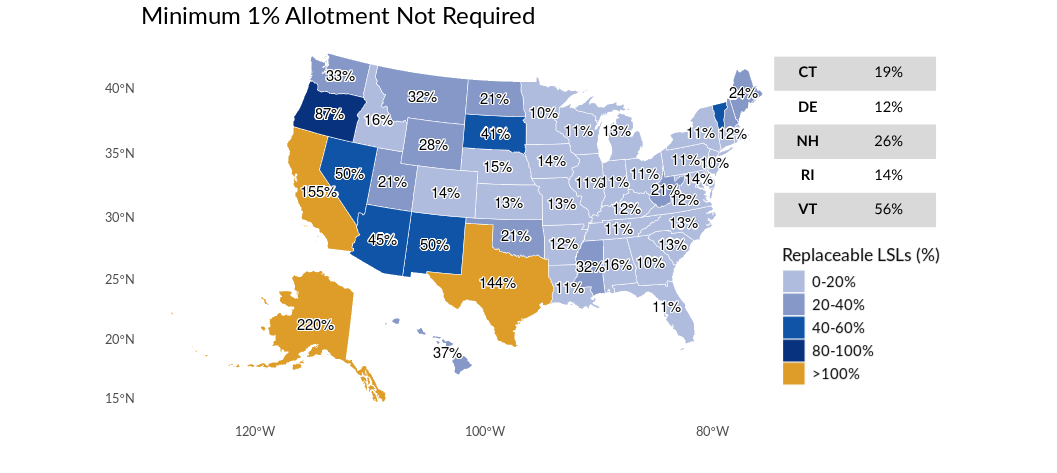

Our analysis shows that removing the 1% minimum cap would have shifted state allotments considerably:

High lead-burdened states would have gained funding

Removing the minimum allotment requirement would have resulted in increased funding for 22 states in FFY23 and 23 states in FFY24. The projected increases in funding range from just under $749,867 to approximately $107 million equivalent to a 2.6%–41.9% boost in funding to states with LSLs. We note there are some exceptional outliers (e.g. Florida) related to potential data inaccuracies of the updated 7th DWINSA, as reported in 2024 by the The Environmental Protection Agency’s Office of the Inspector General (OIG).

In short, without the minimum requirement, funding would shift away from low lead-burdened states that don’t need the funds toward the states with the highest number of LSLs, where every extra dollar translates into communities acting faster on LSL replacement.

Channeling Funds Toward Faster Lead Pipe Replacement

Our analysis shows that removing the minimum allotment cap could yield substantial improvements in funding distribution efficiency by reducing the need for unnecessary reallotments. For states facing the heaviest lead-burdens, that shift could translate into tens of thousands more lead pipes replaced - and safer drinking water delivered - sooner.

In other words, keeping the 1% minimum allotment in place means that states with relatively low lead burdens—particularly many in the West—could receive far more funding than needed to replace all of their lead service lines. For example, Alaska could receive up to ten times the amount required to achieve 100% replacement, assuming an average cost of $12,500 per line.

Waiving the 1% minimum allotment requirement would allow those excess funds from low lead-burden states to be redistributed to those with the greatest number of lead service lines. Ensuring that funding is better aligned with actual need.

With the Lead and Copper Rule Improvements (LCRI) requiring 100% replacement within ten years, aligning funding with actual replacement needs is essential. Waiving the minimum allotment requirement would help cut through unnecessary waiting periods and deliver resources faster to the communities where they can make the greatest difference.

What’s Next

Congress is expected to reauthorize the DWSRF in late 2025 or 2026. That reauthorization could be a pivotal moment to waive the 1% allotment rule for any remaining IIJA LSL funds, including reallotments, freeing up dollars to flow more directly to where they’re needed most.

But let’s be clear: while removing the minimum allotment requirement would be a big step forward, it’s not a silver bullet. More work is needed to refine the allotment formula itself, taking into account:

Total lead burden by state

Inventory completeness

Probability that unknown and unreported service lines are lead

EPIC will continue to dig into these issues and propose actionable recommendations. Because at the end of the day, this isn’t just about funding formulas—it’s about protecting public health, and making sure every dollar counts.

Methodology

Removing the Minimum Allotment Requirement

To estimate how state allotments would shift upon removing the minimum 1% allotment requirement, I first calculated state allotments expected for FFYs 2023-2024 if funding were distributed based solely on each state’s share of the national LSL total (based on DWINSA data), without any minimum caps, via direct proportionality. That is, if a given state were to have 10% of the nation’s total LSLs, then it would receive 10% of the total available funding. These adjusted allotments were then compared with the actual amounts received by each state in the respective FFYs.

To estimate how state allotments would change without the minimum 1% requirement, I calculated hypothetical allotments not subject to such a minimum cap for FFYs 2023–2024. Specifically, funds were distributed strictly in proportion to each state’s share of the national total of LSLs based on Drinking Water Infrastructure Needs Survey and Assessment (DWINSA) data. For example, if a state accounted for 10% of the nation’s LSLs, it was assigned 10% of total available funding. These proportional allocations were then compared to the actual allotments each state received in those years.

I excluded FFY 2022 from this analysis because LSL estimates were not used in that year’s distribution of funding.

Click here to download the data used to compare minimum allotment scenarios.

Practical Implications: Potential LSL replacements

To illustrate the practical impact of removing the minimum allotment requirement, I estimated the percentage of LSLs that could be replaced within each state over the five-year IIJA funding period under two scenarios: with and without the 1% minimum. This calculation followed the methodology used in our prior analysis of EPA’s FFY 2024 allotments.

Click here to download the data used to estimate the percentage of LSLs states could replace under different minimum allotment scenarios.