It’s Time to Invest in a Modern Map of our Nation's Wetlands

The time is right to invest in modernizing our most comprehensive national map of wetlands, the National Wetlands Inventory (NWI). An increase in FY23 funding to $7.47 million, as envisioned by the House, combined with more innovative and cost-efficient mapping methods would accelerate needed updates to decades-old NWI data that is widely used for planning across sectors.

Wetlands are important assets for communities and ecosystems. They offer natural flood protection to cities and towns across the country and are rich in biodiversity, including more than one-third of the United States’ threatened and endangered species. Knowing their location enables planning and mitigation efforts of all kinds, for example, permitting and site selection in the energy and transportation sectors. For decades the NWI, managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, has been a crucial source of information available to the public on the location of wetlands. In fact, the NWI website is viewed about 1 million times annually and last year NWI data was downloaded over 40,000 times.

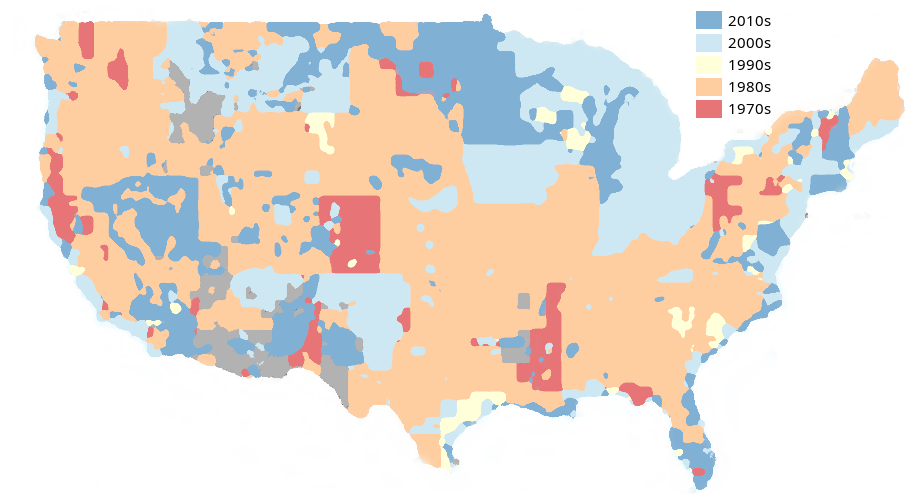

Despite the important roles it plays in permitting, planning, and land and wildlife management contexts, the NWI has not been comprehensively updated for many years. As shown in the map below, much of the NWI map layers actually date back to the 1970s and 1980s, leaving much of the country with an outdated impression of where wetlands exist in their watersheds and communities. This can have real consequences for decision-makers throughout the country. For example, these data are important in the planning stages for infrastructure development projects, such as renewable energy projects and power lines. Bad data can mean added costs of field surveys, or finding out at a late stage that a project will impact more aquatic resources than was anticipated.

Much of the National Wetland Inventory has not been updated since the 1980s. Source: USFWS (https://fwsprimary.wim.usgs.gov/wetlands/apps/wetlands-mapper/)

As a recent letter from Ducks Unlimited has underscored, one of the major reasons for this patchwork of updates has been a lack of funding. Funding for the NWI Program has been stagnant for the past 40 years and, accounting for inflation, the NWI’s current budget is 1/5th of its 1986 budget. This funding stands in stark contrast to assessments of the benefit of these data. For example, others have estimated that the NWI provides the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers $8.25M of savings annually by facilitating Clean Water Act Section 404 permitting. The States of Minnesota and Michigan save $1M and $750K each year, respectively, by using the NWI dataset to support their regulatory review and planning processes. In the private sector, this dataset allows environmental consulting firms to better target their efforts, saving these businesses more than $8M annually.

In addition to declining funding, traditional methods of surveying wetlands are labor-intensive limiting the scale at which NWI is updated. However, new technology-enabled methods could help tackle this challenge and drastically speed up the process of updating it. Efforts to analyze remote sensing datasets from aircraft and satellites using artificial intelligence and machine learning are a promising alternative that have been tried and evaluated in several regions. For example, EPRI and the Chesapeake Conservancy partnered to develop a model that identifies the boundaries of wetlands with an accuracy of 94 percent. Other countries, such as New Zealand, are also investigating these techniques for updating their wetland inventories.

With new methods reaching maturity, there has never been a better time to invest in updating the NWI and establishing a sustainable and cost-effective process for keeping them updated. Doing so will enable cascading benefits to federal, state, and local governments, and industry in conserving and restoring wetlands, and realizing all their many benefits.