Our key findings

Tribal Nations are sovereign governments, with authority and jurisdiction over their lands and waters delineated in the U.S. Constitution, legal doctrine, Congressional statute, executive orders, and treaties. There are 574 federally-recognized Tribes in the United States, and each has a unique drinking water regulatory, ownership, and water delivery structure.

Tribes face a unique set of challenges when it comes to the provision of clean drinking water, and because they are sovereign nations, they have a unique set of solutions for improving drinking water access and quality.

We sought to evaluate existing publicly-available Tribal drinking water data in terms of accessibility, accuracy, and usefulness to Tribes. Through this process, we developed an understanding of:

The roots of Tribal drinking water provision in the federal trust responsibility to Tribes;

The federal agencies that support Tribal drinking water provision;

The complexities of environmental regulatory implementation on Tribal lands;

How those complexities impact Tribal drinking water data collection and reporting by federal agencies;

The cascading effects of federal data limitation in terms of Tribal drinking water access; and

The opportunities presented by Tribal data sovereignty in addressing the Tribal drinking water access gap.

Just as Tribes were left out of this country’s first environmental laws, including the Safe Drinking Water Act, they were left out of the infrastructure funding that came with the passage of those regulations. Several years after funding declined markedly, environmental regulations were extended to Tribal lands, and Tribes have been playing catch up ever since. The original omission of Tribes from environmental regulations is mirrored in the omission of Tribes and Tribal priorities from drinking water data and drinking water research.

First, some things you should know:

-

In research that is not specifically Tribally-focused, statistics about Tribal water access are often presented alongside statistics about rural water access and access among communities of color. While Tribes often face many of the same challenges these communities face, they also face numerous other complexities and challenges, operate within a different regulatory structure, and operate in an entirely different political landscape. Tribal sovereignty and the federal trust responsibility means that Tribal leaders have an entirely different set of tools to improve drinking water access. A cursory nod to broad statistics about “Native Americans” ignores the fact that there are 574 Tribes across the United States–each with entirely unique governance, regulatory, and legal structures. Trotting out the dire statistics of Tribal access to water while failing to address the political realities that have produced these statistics results in policy solutions that are useless to Tribal communities and furthers misconceptions that flatten Tribal communities. Dive deeper into the drinking water issues Tribes face here, here, and here.

-

Tribal sovereignty extends to data about their citizens and their lands., There is a long history of misuse and theft of Tribal data, mainly by the federal government and researchers, toward ends that have done Tribes great harm. A growing movement among Tribes to assert sovereignty over their data has resulted in increased protections by Tribal governments for data reflected in a growing body of Tribal laws governing data sharing with outsiders. Data sovereignty scholars have highlighted how federal data collection processes, stipulated in federal regulations and grant reporting requirements fail to account for community needs and result in a “one-way data highway,” where Tribes report data to federal agencies and never get it back. The data sovereignty movement includes efforts to protect data and calls for the inclusion of Tribal needs in federal data collection and report-back processes and offers opportunities for Tribal data innovations to meet Tribal priorities.

-

Two federal agencies–Indian Health Service (IHS) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)–maintain Tribal drinking water datasets (STARS and SDWIS, respectively), and only a portion of what is reported is made available in public data sets. Census demographic data, sometimes linked with drinking water data to assess Tribal drinking water access, has historically undercounted American Indians and Alaska Natives living on reservations. Tribal governments, who maintain enrollment data on all of their citizens, typically do not participate in validating Census data. Tribal governments often collect more data and may have alternative ways of collecting data that operate outside of conventional federal agency data collection methodologies. Moreover, growing bodies of Tribal laws govern the protection and sharing of this data–many Tribal Nations have their own IRBs or alternative data governance processes–and are open to and interested in sharing data with researchers, provided the research adheres to Tribal guidelines and is used appropriately.

-

Our analysis shows that only 56.6% of Tribes have land that overlaps with a CWS–folks in areas without a CWS are probably hauling water from wells or from other types of public water systems. Our analysis also found that Tribes are disproportionately impacted by water quality violations–about 7% of these CWSs have an open health based violation, compared to 2% of systems that don’t intersect with Tribal lands.

There are limitations when it comes to EPA’s new Service Area Boundaries (SABs) dataset and its accuracy on Tribal lands. SABs is composed of state-reported system boundaries and modeled boundaries which were validated with state-reported data. Thus, Tribes and Tribal data were not included in the creation of the dataset, or in the validation of the dataset.

However, if improved in collaboration with Tribes, the SABs data could be used to estimate well use, to understand drinking water access and quality variations within Tribal lands among Tribal and non-Tribal populations, and could help IHS staff improve community deficiency profiles in IHS STARS data.

Here’s what we found

-

Some EPA data filters used to understand Tribal drinking water access lack clear and consistent definitions across EPA webpages and data dictionaries (see definitions here, here, and here), or are missing meaningful definitions (such as the Native American owner category in SDWIS). Additionally, EPA data caveats–the documents accompanying datasets and explaining potential errors or limitations–often do not include any meaningful description of Tribal data limitations. The primary data caveat related to Tribal data is the Tribal Lands Data Quality Caveat, which pertains specifically to the accuracy of Tribal boundary data represented across EPA datasets. There are few descriptions of how Tribal data is inaccurate, and data caveat descriptions either omit Tribes (such as ECHO Known Data Problems and the SABs Dataset Summaries), or provide limited detail (such as the SABs Fact Sheet).

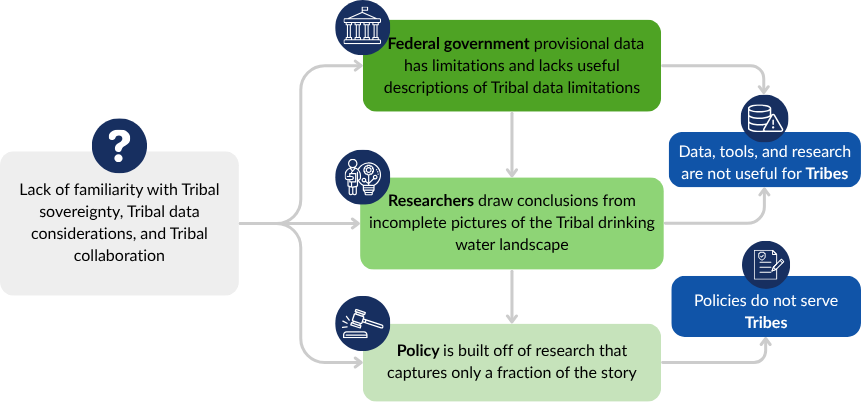

We found that, as a result, researchers working with these data do not always have a complete sense of the limitations of the data and may even interpret the definitions of Tribal indicators in the data differently.

The Indian country indicator (via the ECHO Facility Search) and/or the EPA Area Type/Tribe Name indicators (via the SDWA data download, and/or the Tribe Name filter (in the Drinking Water Dashboard) can all be used to understand drinking water access on lands where Tribes exert their sovereign authority. Using this indicator requires careful efforts by researchers to communicate that these filters don't tell researchers anything about who is served by these systems, and data users may not know that the filter omits some systems that are not considered Indian country in SDWIS system due to jurisdictional particularities or data entry errors.

The Native American owner type (via the SDWA data download) has been used to understand Tribal drinking water access, but it lacks a meaningful definition in any public SDWIS data dictionary–some researchers have interpreted it as referring to Tribal government-owned systems, and others have equated it as encompassing systems that serve Tribal lands.

-

In recent years, EPA has been working to improve its relationships with Tribes, including through the hiring of Tribal-focused staff and through the development of the Tribal-specific section of the drinking water dashboard. Still, SDWIS data and associated Tribal filters seem convenient for understanding Tribal drinking water, but data users should be cautious in drawing broad policy conclusions from SDWIS data, and should approach the data with an understanding of Tribal sovereignty and drinking water governance. The data limitations we identify below are the result of the omission of Tribal data in data dictionaries, data caveats, data entry errors, and Tribal jurisdictional complexities.

When it comes to Tribal drinking water data, EPA datasets and publicly-accessible data tools omit Tribal water systems that are unregulated or not considered “Indian country” by EPA:

Tribal systems are more likely to be unregulated, and thus not captured in SDWIS data. For example, “Native American households are more likely to lack piped water services than any other racial group,” and must haul water from wells, which are not regulated by EPA if they serve fewer than 25 individuals, and thus are not captured in SDWIS and subsequent research. We describe how the particularities of water distribution in Indian country compound to result in limited EPA SABs data for Tribes in particular here.

Our analysis using SABs data, which is likely inaccurate for Tribes, but is the only existing proxy, suggests that as much as 43.4% of Tribal lands are not served by a CWS.

The SDWIS Indian country indicator and other Tribal indicators fail to capture some systems that serve Tribal land and Tribal citizens–sometimes because of data entry errors and sometimes because of jurisdictional specificities. While the filter can be a useful proxy, particularly when evaluating drinking water where Tribes have the most authority and political influence to improve drinking water access, endless jurisdictional and legal complexities that can’t easily be mapped onto the SDWIS classification scheme can result in the omission of some water systems or entire Tribes from any Tribal indicators.

Based on our preliminary analysis, only 53% of water system Service Area Boundaries that intersect with Tribal land contain the SDWIS Indian county flag. That means that 47% of systems intersecting with (and potentially serving) Tribal land are not captured when filtering ECHO reports for the Indian country flag. This analysis is of course preliminary and relies on the Service Area Boundaries data, which has its own issues when it comes to capturing data on Tribal land.

-

EPA priorities inform EPA data collection and classificationsystems, which result in EPA-provided trend analysis tools that are not necessarily reflective of the most relevant variables that impact Tribal drinking water access or of the data that Tribal staff care about.

SDWIS classification schemes that are not designed for Tribes result in datasets and tools that do not accurately capture Tribal drinking water systems and can be difficult to use. An unknown amount of Tribal drinking water data is excluded from data systems or Tribal filters, and this is compounded by missing or incomplete data dictionaries, and a lack of Tribal representation in data caveats. The jurisdictional complexities of Tribal systems mean that Tribal data is most in need of thorough descriptions of data caveats. Data users looking into Tribal drinking water data are thus left to spend additional research time wading through data and making sense of discrepancies using scarce documentation.

Lack of a shared vocabulary among researchers and complexities of Tribal data can be flattened in secondary and policy research. The results of the SDWIS classification issues are evident in researchers’ varying definitions of “Tribal drinking water system.”

Tribes are not included in the development of datasets and tools, and thus products are not relevant to Tribal leaders and staff. Tribal drinking water departments are already underresourced, and that’s worsened when they aren’t able to access or use the same data analysis tools and policy research that other communities are.

-

EPA’s data on Tribal systems captures systems within the federal definition of Indian country and is limited to EPA’s regulatory scope. The data captured in STARS captures a different geography from what is captured in EPA’s SDWIS dataset. IHS data includes only “Indian homes” (excluding other buildings such as schools and offices) in “Indian communities” but lacks a regulatory definition of “Indian community.” Its geography, then, is more extensive than EPA’s “Indian country” geography, but is also more fragmented–excluding any non-home structures and any non-Indian homes within Indian communities.

Then there are the geographies that Tribal leaders, drinking water operators, and Tribal citizens might care about that are not captured in EPA and IHS data analysis tools, such as places outside of formally federally-recognized Tribal lands where Tribal citizens live, work, attend school, hunt, fish, exercise treaty rights, or have ceremonies–anywhere Tribal citizens might be drinking water. A Tribal drinking water operator expressed to us the importance of having an understanding of drinking water quality and access throughout their watershed, particularly given the increasing prevalence of PFAS water sources and for climate change resilience planning.