Tribal Drinking Water–The State of the Data

To develop meaningful solutions, you must meaningfully define the problem

Vision

Tribal communities should have access to safe, reliable, and affordable drinking water.

Problem

The statistics on Tribal drinking water access are dire–nearly 50 percent of Tribal homes on Tribal lands lack access to reliable water sources, compared to 1 percent of U.S. homes overall. But that number only tells a piece of the story.

Solution

Our investigation uncovered a Tribal drinking water data gap–if we can’t define the drinking water access challenge, we can’t solve it. But our research also uncovered that we have the tools to bridge the data gap–we just have to do it!

Start here

Don't know what we're talking about? Get oriented here.

Ready to dig in? Here's what we found.

Ready to be part of the solution? Here's how we bridge the data gap.

Want details? Explore the data yourself.

Piecing together the Tribal drinking water data puzzle

Tribal sovereignty, land tenure, and jurisdiction are often not well understood outside of Tribal communities. To address Tribal drinking water needs, solutions need to account for Tribal sovereignty, Tribal water system governance, and Tribal regulatory implementation. But that’s hard to do when the data we use to define Tribal drinking water doesn’t capture the reality of drinking water governance.

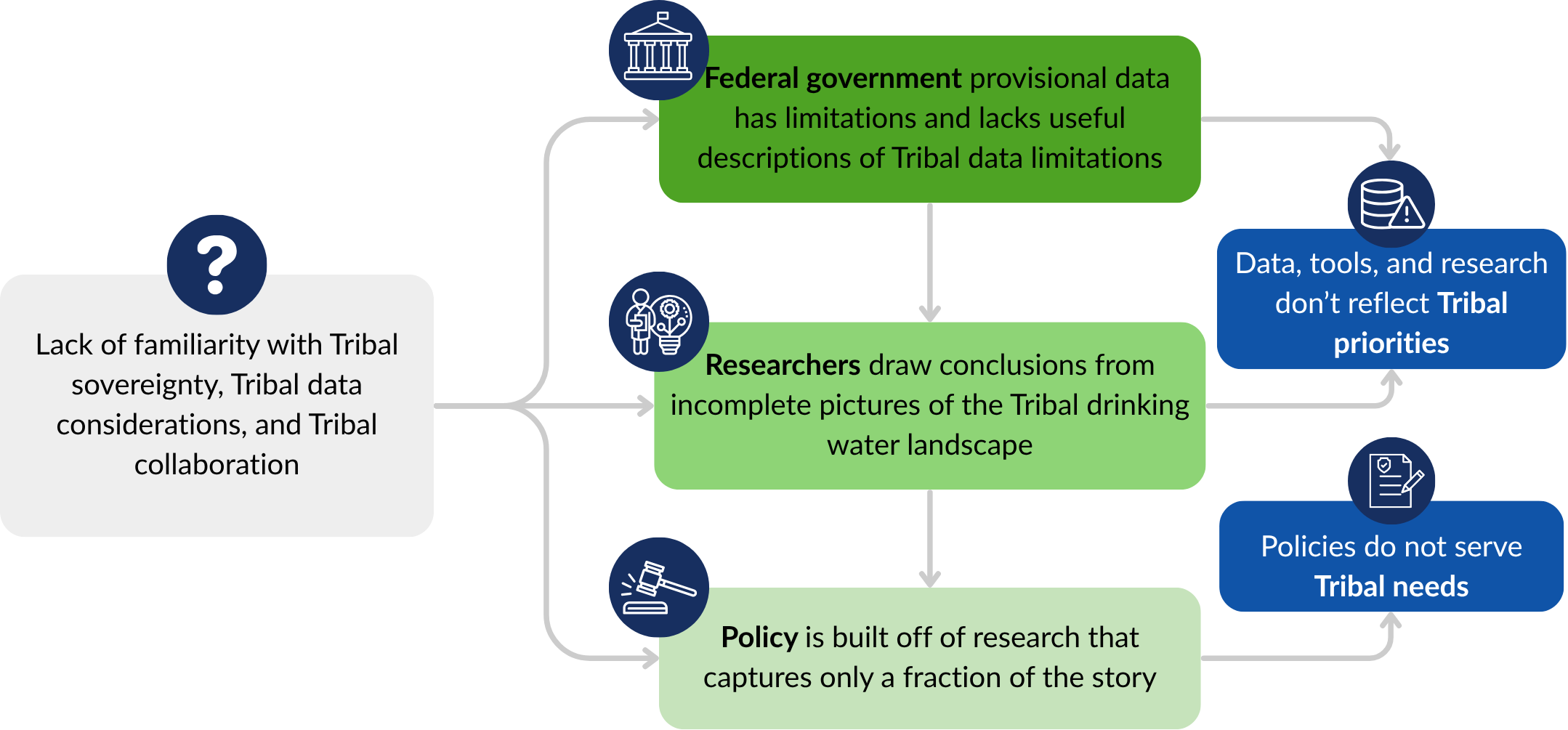

EPIC undertook an effort to evaluate publicly-available Tribal drinking water data as it is provided by EPA and Indian Health Service–the two federal agencies that collect and maintain Tribal drinking water data. We also sought to understand how data functions as a strategic resource for Tribes seeking to address drinking water challenges . We found that publicly-available Tribal drinking water data is difficult to access, inaccurate, and lacks definitional clarity. In turn, Tribal staff, researchers, and policymakers are working with data that only tells part of the story of Tribal drinking water access. The result is data, tools, and research that are not useful for Tribes, and policy solutions that do not serve Tribes.

Our findings signal that Tribes continue to be an afterthought in the broader landscape of drinking water regulatory data and research, and this has cascading effects. If Tribes are left out of the data, how can we expect them to be included in the solutions? Just as the federal government has a trust responsibility to provide sanitation and drinking water to Tribes, the federal government has a trust responsibility to provide Tribes with relevant data and analysis tools that are useful, accurate, and consistent with Tribal data sovereignty.

Let’s get oriented

Tribal drinking water governance and data are complicated and so as we get into this, there are several terms and governing policies that define this landscape.

-

Tribal sovereignty is the inherent right of Tribes to make their own laws and self-govern. Their sovereignty is inherent, and is not granted by the United States (which is how states are able to exercise sovereignty). The federal government recognized Tribal sovereignty in the U.S. Constitution.

Tribal sovereignty means that “Tribes possess all powers of self-government except: (1) those relinquished under treaty with the United States; (2) those that Congress has expressly extinguished; and (3) those that the federal courts have ruled are subject to existing federal law or are inconsistent with overriding national policies. Tribes, therefore, possess the right to form their own governments; to make and enforce laws, both civil and criminal; to tax; to establish and determine membership (i.e., tribal citizenship); to license and regulate activities within their jurisdiction; to zone; and to exclude persons from tribal lands.” -

“‘Indian country’ is the territorial area over which tribes have jurisdiction. It was defined by congressional statute in 1948 to include reservations, dependent Indian communities, and allotments.” This seems simple, but the three exceptions to Tribal sovereignty identified above have created an incredibly complex landscape of Tribal governance and jurisdiction.

There are a variety of land ownership structures in ‘Indian country’––a phenomenon called ‘checkerboarding’–and a variety of ways that Tribal sovereignty over particular land types may be limited. Even though the Federal government’s definition of Indian country includes all land within the boundaries of a reservation, Court and Congressional intervention has limited Tribal government jurisdiction depending on the legal realm (civil or criminal), people involved (Indian, Tribal citizen, non-Indian), and parcel land status (trust land, allotment, fee simple). The result is that, sometimes, jurisdictional issues have to be resolved before a problem can be dealt with. When Tribes are forbidden from asserting their sovereignty, it is the job of the federal government (usually) to step in. Federal jurisdiction doesn’t always mean the federal government is prepared to respond–federal agencies are used to operating programs at the federal level, not a local level. There are myriad consequences of these jurisdictional gaps, including the crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous women as well as the enforcement of environmental regulations, where major threats to public health can fall under the radar, obfuscated by jurisdictional confusion.

You can learn more about the history of federal Indian law here, here, and here.

-

Tribal sovereignty extends to Tribal data., In the context of drinking water, this means Tribes have the right to keep drinking water data confidential. Tribes have the right to own, steward, and govern their data. Just as Tribes have the right to collect and maintain data, they have the right to decide who to share it with and how. Often, Tribes have much better drinking water data than is publicly-available, and through direct engagement with Tribal governments according to their data sovereignty laws and policies, approved researchers and partners can develop deeper understandings of the realities of Tribal drinking water access. The Tribal data sovereignty movement comes out of long histories of data theft and misuse by the federal government and by researchers.

As Tribal data sovereignty scholars have pointed out, federal data collection processes often leave Tribes out, and “the result is that Indigenous nations rely on external data that largely fails to reflect community needs, priorities, and self-conceptions…[which] threatens self-determination, limits informed policy decisions, and restricts progress toward Indigenous aspirations for healthy, sustainable communities. Likewise, reliance on this data by researchers and governments limits the robustness of data-driven research and the validity of policy decisions.” Tribal data sovereignty scholars note that Tribes rarely get this data back, and when they do, it might not be particularly useful. Researchers have characterized this as a “one-way data highway.” You can read more about Tribal data sovereignty and drinking water data here, and find resources related to data sovereignty and governance more broadly here.

-

In exchange for vast amounts of land and resources, through treaties, executive orders, and laws, the United States promised to provide Tribes certain protections, services, and to honor and uphold their sovereign status and reserved rights.

Since the 1831 Supreme Court decision, Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, which characterized Cherokee Nation as a “domestic dependent nation,” the Court has continued to hold the federal government to its responsibility to Tribes as that of a trustee–the United States is required to uphold its end of the deal and to protect Tribal assets for the benefit of Tribes. One of the duties of the United States is to provide for the health of Tribal citizens, which includes the provision of drinking water and sanitation infrastructure, implemented principally through the IHS Sanitation Facilities Construction program, but also provided for in other federal programs administered by other federal agencies. -

EPIC’s Tribal drinking water data evaluation assessed the state of Tribal drinking water data collected, maintained, and reported by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and Indian Health Service (IHS). Though there are at least seven federal agencies that support Tribal drinking water infrastructure projects, only IHS and EPA collect and report data on Tribal drinking water needs. EPA is authorized by the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) to regulate drinking water nationally, including on Tribal lands. EPA maintains the data necessary to effectively implement SDWA in the Safe Drinking Water Information System (SDWIS). IHS, an agency within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), was created to carry out the federal government’s commitment, reserved by Tribes in treaties in exchange for land and resources, to provide public health services to Tribes, including drinking water and sanitation infrastructure. IHS implements this responsibility through its Sanitation Facilities Construction (SFC) program, and maintains the data necessary to carry out this program in its Sanitation Tracking and Reporting System (STARS).

-

Researchers, particularly those working with an environmental justice lens, frequently identify water access gaps for particular populations by linking Census demographic data with geospatial boundaries of SDWA data (either by approximating drinking water customer areas according to drinking water system facility locations or using the EPA water system service area boundaries data). This type of analysis can be useful, but Census data historically undercounts Native populations, particularly those living on reservations, and Native people are frequently misclassified in vital records.

-

A public water system (PWS) is defined in the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) as a system that provides water for human consumption to 15 or more connections or regularly serves 25 or more people daily for at least 60 days out of the year. A water system is not the same as a water utility–”a water system is a discrete regulatory unit subject to drinking water standards promulgated by the federal government and state primacy agencies..and can consist of connected components, such as water wells.”A utility could own multiple, and in the case of large utilities hundreds, of water systems.

There are three types of PWSs:

A community water system (CWS) is one of three types of PWSs. It is defined as a public water system that has at least 15 service connections that serve year-round residents or that regularly serves at least 25 year-round residents.

A nontransient noncommunity water system regularly supplies water to at least 25 of the same people at least six months per year—for example, in schools, factories, office buildings, and hospitals.

A transient noncommunity water system provides water in a place where people do not remain for long periods of time—for example, a gas station or campground.

-

A key component of SDWA is the Public Water System Supervision (PWSS) program–essentially the mechanism by which the agency tasked with enforcing SDWA, or primacy agency, ensures that drinking water systems are meeting the SDWA standards. Through the PWSS, the primacy agency must collect and report drinking water data to the EPA via SDWIS. States and federally recognized Tribes may apply to the EPA for primacy to implement and enforce SDWA, so long as the PWSS program is adequate to enforce the requirements of SDWA. If Tribes choose not to exercise that authority, then the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (not the state) directly implements SDWA on Tribal lands.

What we found

The state of tribal drinking water data

Better Data is Possible

Here’s how we can bridge the data gap →

Through this research effort, we identified solutions to the data gap that are grounded in the framework of Tribal data sovereignty and seek to:

Bridge the data gap: We have disparate datasets and tools, and they aren’t meeting Tribal priorities, but through Tribally-led initiatives, we can put the pieces together to bridge the data gap. Our recommendations identify opportunities that rely on data sovereignty frameworks to use existing data, collaborative models, technology, and data sharing to build better Tribal drinking water data.

Build knowledge: Outside of Indian country, the particularities of Tribal governance can get missed in national-scale drinking water research. Data collection systems miss pertinent factors, data descriptions omit the limitations of Tribal data, and, ultimately, research and policy recommendations don’t serve Tribal priorities.